Fame & Misfortune

We need more mediocrity in government

Fame. Makes a man take things over.

What if, instead of using petitions, states drafted people to serve in candidate pools for state and federal elections? It would help resolve the problem of the political cartel that ruined America. I suspect it would also end up changing the way we allot resources—in part because for the first decades there would be at least a 20% chance that anyone selected to run will be functionally illiterate.

There already is one element of governance given over to the general public—juror service—to determine criminality or culpability, through the Judicial.

But people have jobs and lives is the first critique of the idea of a candidate draft. Yes, we would have to come up with some means of protection, just like with juror service. We don’t want people becoming unemployed for their service to the public, running for and possibly winning office. Unlike juror service, we could give those selected for the candidate pool (people will still have the chance to vote) the ability to opt out. But we could easily compile a field of 6 or 8 candidates for most offices.

Unironically, opening up candidate pools will mean the end of amateurism in political office. We will have to turn those remaining unpaid positions into ones paying at least a living wage.

Amateurism as a rule for participation in both NCAA athletics and the Olympics were merely insurance against social class integration. Leisure time has never been fairly distributed, and amateurism was a cultural shortcut to banning the working class. It operates in the same fashion in those political districts that mandate it.

Unlike juror service, which is seen as a burden to the majority of the population, winning an election will mean an income boost if most states and the federal government keep current salary and benefits rates. Hell, we are likely to see a bunch of newly-elected Representatives get long-delayed dental work and other medical care, once they have coverage.

But they won’t know what they are doing, is the second critique. This makes it sound like the folks currently in office do know. We should be careful not to ascribe competence to confidence. Look at what that has done to us, so far.

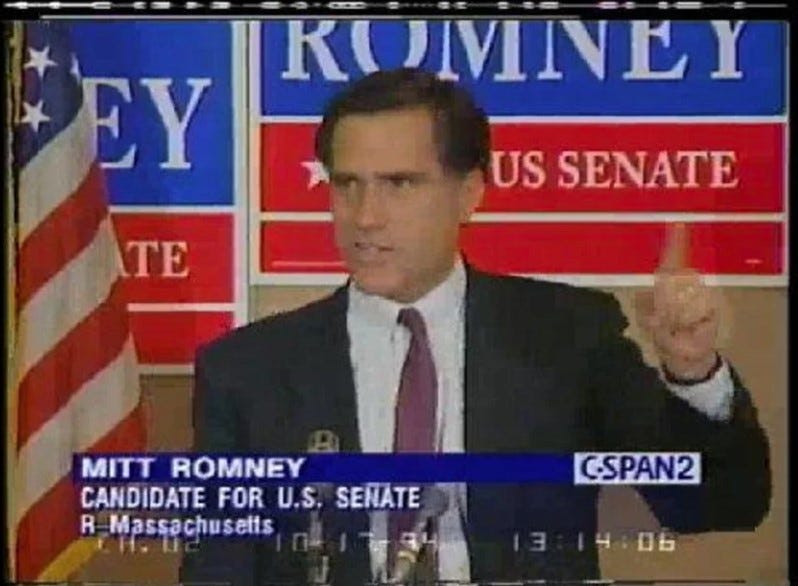

Multi-millionaire Mitt Romney’s own first foray into politics (his father, George, was Governor of Michigan and once an erstwhile Republican contender for the Presidential nomination) was in 1994 for a Massachusetts U.S. Senate seat. His campaign was lost after The Boston Globe published an interview with his wife, Ann, recalling their “struggle” as a young couple with a “basement apartment on Beacon Hill” (Boston’s wealthiest neighborhood) that had to “sell stock” in order to meet expenses.

He later ran for Governor of Massachusetts and won. Then he ran for President and lost. Then he ran for the Senate again, and this time he won—in Utah. He went 2 - 2 for four seats, in three electoral districts.

Seldom does a candidate branded from their work outside of politics run for low-level office. Mitt was not going to waste time running for state representative or county commissioner, building a network of supporters and political insiders to help improve the quality of life for the people in his adopted hometown of Belmont, MA. Why bother, when you have enough money to buy the signatures you need to take an entry-level position in politics as a U.S. Senator?

Elections are not about branded candidates knowing what they are doing—they are about winning campaigns, and that has nothing to do with governing.

As the military draft evolved into a concern about the ongoing physical fitness of teenage boys, a candidate draft will turn our attention to being sure high school graduates have already been provided sufficient resources to be able to do the job, when called upon.

We have a cultural tendency to focus on the positive, second and third standard deviations from the norm, and call them evidence of merit. We favor the meritorious, offer them higher status, and believe they can produce in the public body semblances of their own merits.

Rich people will help the economy and make everyone richer. Smart people will know how to approach and address social problems and improve the quality of life. Strong people will show us how to become more physically fit.

First, if these individuals are expressing some form of genetic difference (perhaps even a racial difference) then they have nothing to offer the society as a whole, since what they are expressing is not transferrable, and ultimately not even their own doing. The genetically-gifted are not useful for improving the general welfare.

Second, if these individuals are expressing some form of personality or character difference they can be seen as role models, but biographical differences guarantee that no one else will be able to have quite the same generosity, gregariousness, or self-sacrifice.

Individuals expressing merit earned through discipline and training offer the most shareable and teachable quality to others. This leads to a question of opportunities: How much time and what resources were required?

Is what we perceive as merit mostly evidence of prior inequalities, earned or unearned?

Public health, like literacy, is best understood from the least-common denominator. Our public literacy, like our public health, cannot be improved by focusing on the outliers as examples, or expecting the outliers to be able to transfer what made them outliers, to the populace as a whole. Logically, it is a statistical impossibility.

What makes people outstanding in politics is not what makes for the improvement of the general welfare. For that, we would be better off using random assignments.