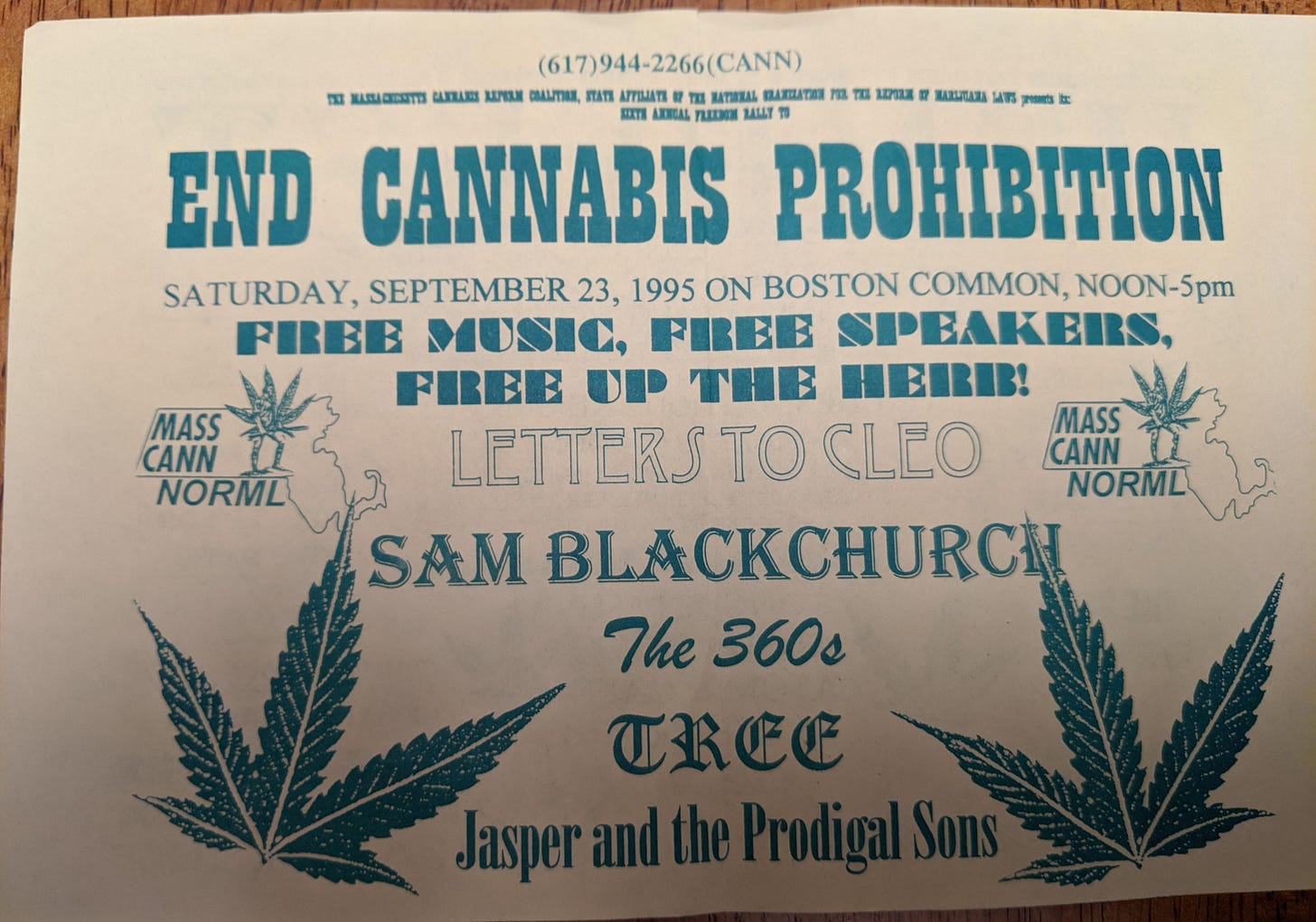

Freedom Rally Artwork - II

The challenge of an acquisition in the here and now

In 1985 Australian magnate Rupert Murdoch became a U.S. citizen, allowing him to own broadcast television stations. In 1986 he launched the FOX network, which addressed the three national networks’ domination of the airwaves by targeting the audiences they had been ignoring: African-Americans and teens, in particular. The new network was also willing to utilize UHF frequencies (the “ghetto” of TV broadcasting), and debuted shows while the others were in reruns.

Once upon a time, networks would debut their new “seasons” in September. Weekly shows produced about 26 episodes per season, with shows being rerun through the late spring and summer. The “Book” (audience counts translated into advertising rates) was set via measurements taken in October and February, through the Nielsen Company, which specialized in broadcast media market polling. By debuting shows in the summer, FOX gained viewers, but they went unmeasured.

Along with the rise of FOX TV, the 1990’s began the mass consolidation of American media. Deregulation by the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations brought larger swaths of “local” newspapers, radio stations, and other media, under fewer corporate umbrellas.

Mass media conglomerates formed, which for example would control a national TV network, a collection of FM radio stations (each branded “KISS,” e.g.), book and periodical publishers, and a record company.

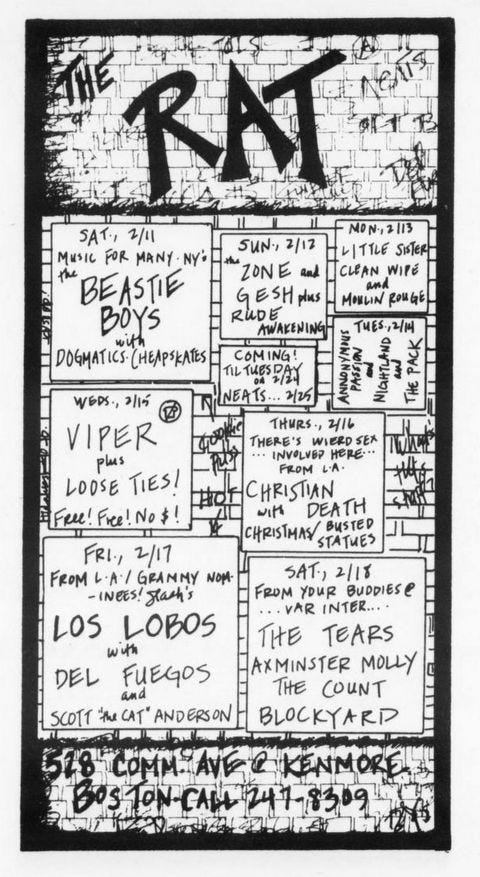

The 1990’s was also the declining days of the Boston Music Scene. By virtue of multiple schools of music (Berkeley, in particular) and a huge college student-aged population, Boston produced a large selection of musicians and bands that went on to national acclaim. The city’s #1 rock radio station, WBCN (independent from its founding in 1968 until the middle of the 1990’s), launched multiple bands. Bands performing in small or tiny venues would catch a DJ’s attention and the radio station allowed them the freedom to play undiscovered music.

Having your song played to a potential audience of 250,000 college students from around the nation made it possible for bands like Aerosmith and U2 to go from playing The Rat in Boston’s Kenmore Square to football stadiums across the country.

Letters to Cleo was such a band, made up of Boston locals and playing gigs in the area, they caught some attention and were signed to a small, independent label out of L.A. That label was bought by a larger company that had a relationship with the FOX network, which was going to be debuting a new show in the summer of 1995, to follow their recently-established Beverly Hills 90210. Instead of being set at a high school, this show would follow a similar, ensemble cast of early 20-somethings (FOX marketed to Gen X while the other networks ignored them) living at Melrose Place. As has become the case, post-conglomeration, the TV show would also be used to sell a soundtrack—this one featuring “Here & Now” by an unknown band out of Boston.

This video closed every episode of Melrose Place that summer. By September, most college students returning to Boston (or arriving for the very first time) had heard of Letters to Cleo.

The localized, state-based scope of marijuana policy reform made partnerships with local performers for the sake of mutual promotion a natural fit. MassCann had a years-long relationship with WBCN, with the radio station offering a performer set on the Boston Freedom Rally stage as one of the prizes for winning their annual Rock n’ Roll Rumble—a local music competition. ‘BCN played Letters to Cleo before they were on TV every week, and the station continued to do so, alongside promotions for the Freedom Rally.

The 1995 Sixth Annual Freedom Rally headlined Letters to Cleo—made possible because MassCann members and band members were friends. The Boston Police Department estimated 1995 Rally attendance at over 100,000 people.

The harmonic convergence of macrosocial forces and personal networking established the Boston Freedom Rally as a viable means of getting a legalization message out like never before. It was still in the days of corporate monopolization of news; we were a decade away from attempts to livestream the Freedom Rally or otherwise allow MassCann to produce its own media. By drawing such a large crowd, MassCann showed it had to be taken seriously as a public voice, and that marijuana legalization was coming back into popular support. It would be another year before California voters approved Prop 215, creating the first medicinal marijuana legalization.

The 1995 Freedom Rally guaranteed future local TV coverage, for as long as the event drew a crowd. It was a compromise, as the slant of TV reporting was to marginalize attendees and make bad puns, but having a snippet of a legalization message broadcast was a big step forward, after over a decade of Just Say No(thing).

For the next decade the purpose of the Freedom Rally, besides fundraising, was to create a newsworthy event and hope to have a little of the pro-legalization messaging get through the broadcasters’ filter. The gigantic crowd in 1995 (and later) meant MassCann could attract sponsorships that would cover production costs and ensured the coalition’s ongoing operation—soon to branch into running Public Policy Questions in dozens of Massachusetts Representative and Senatorial districts, largely funded by Freedom Rally revenues.

#BankruptElon