“How do you know there is a social movement to reform marijuana laws?”

I had to answer this question early in my quest to understand marijuana in the United States, at the end of the twentieth century. What makes a social movement, and what evidence is there of social movement?

Evidence must be empirical; the Scientific Method was the original “Fuck your feelings” perspective. What historical and material elements prove this thing exists?

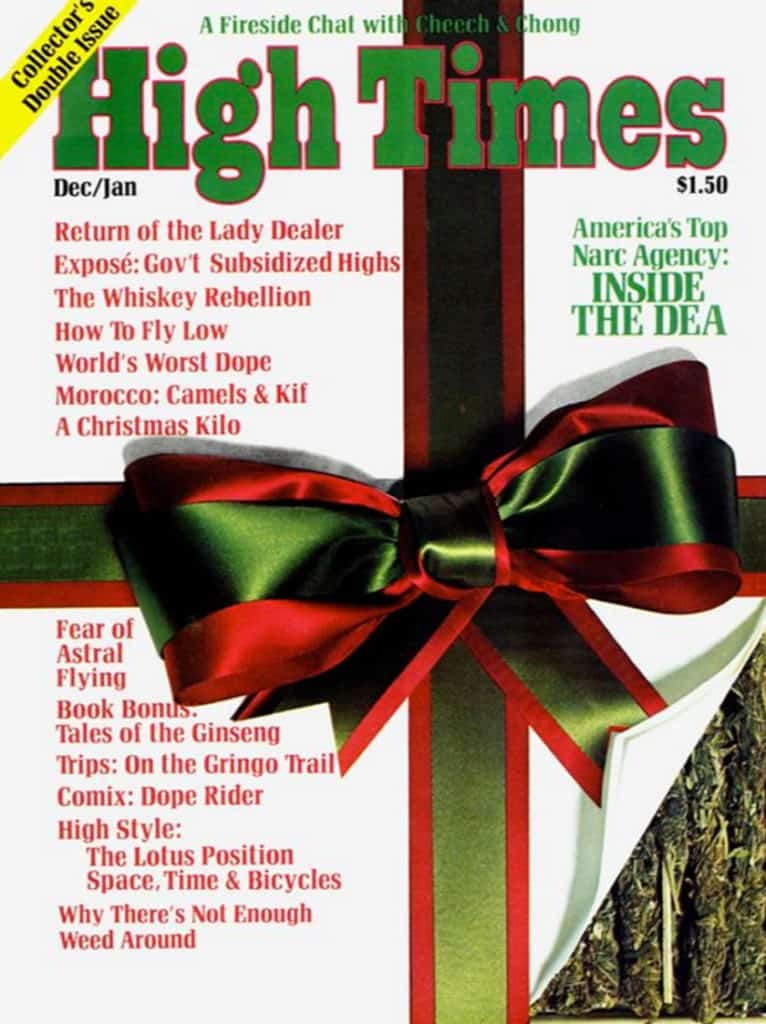

The strongest evidence for social movement was historical documentation of resources having been put into motion for stated purposes by a regular cast of actors. The marijuana reform advocates had been producing this for decades, and since 1974 a lot of it was recorded in High Times.

On October 26, 1989, Operation Green Merchant went down. Forty grow shops had their records seized by the DEA (almost all of the growing equipment advertised in the magazine can be mail-ordered) and the High Times officers were subpoenaed (High Times No. 289, Sep 1999, p. 41). The magazine successfully fought the subpoena and used the harassment as fuel for an "Us or Them" call to readers to step forward and be active.

People in the marijuana policy reform movement had been advancing the commercial hemp and medical marijuana positions, separating these aspects of cannabis use from recreational ingestion, searching for a way to achieve their goals outside of that near-bankrupted framework. Meanwhile, marijuana consumption persisted, the market showing enough promise for a domestic growing industry to invest in shifting a larger proportion of the operations indoors, the very action that Green Merchant was supposed to allay. There have been intense domestic marijuana eradication efforts put forth since the earliest years of the Reagan drug war. As the risk of having an outdoor garden detected by the DEA, National Guard, State Police, Sheriffs or local police (as well as the pot thieves that have always plagued outdoor growers) increased it was a rational response for small-scale, dedicated marijuana growers to move operations indoors, where they are more difficult to detect.

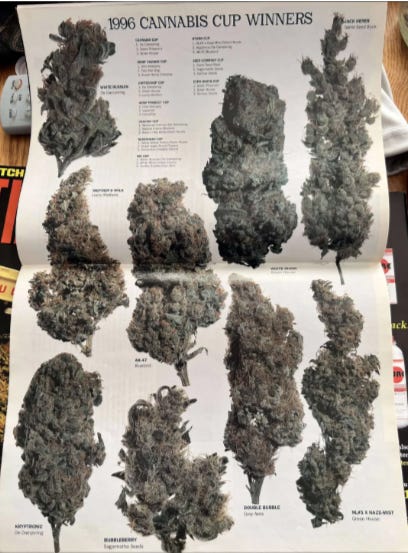

The extra benefit of a fully controlled environment served to maximize growers' influence on the qualities of the marijuana produced. There is recognition in both High Times and among members of marijuana culture that there is a greater variety of potent strains of marijuana available in the U.S. now than ever before. Indoor growing has produced boutique marijuana—and there remains a steady supply of commercial, outdoor grown, imported marijuana that is laden with seeds, often bricked, and tinged with the ammonia of degrading organic material. Boutique marijuana is given "brand" names (i.e., White Widow, Northern Lights, Blueberry Bud, Purple Haze, Jack Herer, Strawberry Cough, Skunk, Big Bud).*

*Footnote 16: The naming of strains of marijuana can be traced to distribution networks prior to the popularization of marijuana. Michael Aldrich (1980) indicates that in 1965 the LEMAR Newsletter identified strains by the names "Acapulco Gold" and "Manhattan Silvertip." Also from the late-60's/ early 70's there was the presence of"Panama Red," "Columbian Gold," "Maui Wowie," and "Thai stick." The indicator of the alleged place of origin was short-lived in the conceptual geography of marijuana culture; the terms of the pre 1960's were generic ("Grass," "Tea," "Weed," "Muggles"), and by the late 1980's the identification by origin, while still made on occasion, was no longer common. The exoticism of identifying the location of origin was rapidly supplanted by the focus on the genetics of the strain-since the indoor growing conditions were far closer to uniform than the climates of the globe, the naming of marijuana would be granted to the breeders.

—Saunders (2002), Pp. 191 - 194.

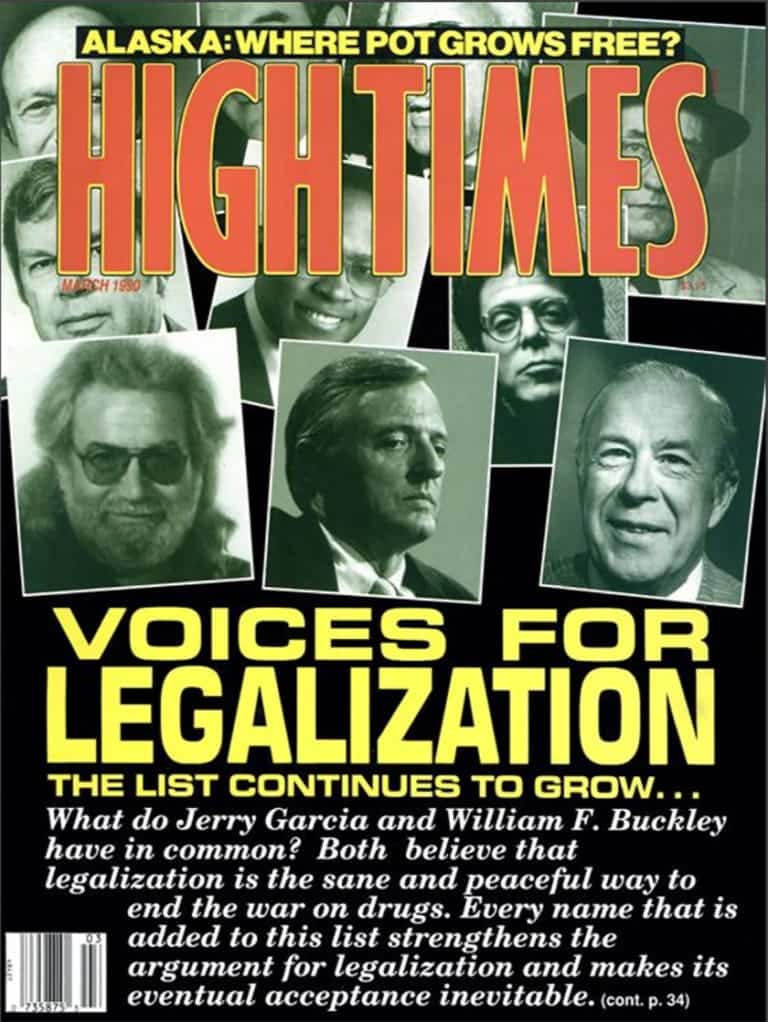

Editorially, High Times’ response to Operation Green Merchant was to fight back. The magazine featured increased coverage of citizen activists who were working to change marijuana laws, along with those celebrities who were still cool with weed and legalization (a risk to one’s career at the height of the Reagan/Bush Drug War), and culture pieces about consumer products, music and fashion, and the signs and symbols of resistance to marijuana prohibition.

Of particular cultural significance was The Cannabis Cup and the magazine’s centerfold. The Cannabis Cup was an international competition to find “the best” cannabis flower and THC-containing products. It was staged for the first couple decades in Amsterdam, likely the only city in the world where the open violation of cannabis laws by a horde of American stoners and their European brethren would be tolerated. By the end, even the Dutch grew weary of the World’s Greatest Pot Party and arrested longtime organizer and magazine editor Steven Hager for cannabis possession well in excess of Amsterdam’s most liberal tolerances.

By then, medicinal laws and creeping legalization in the U.S. made staging cannabis cups closer to home feasible, and High Times took up the pursuit in the 2010’s as a means of expanding the brand. While print periodicals faded, High Times put more resources into Cannabis Cups, diluting the event’s claim to define what was world-class-quality weed. Later incarnations of the High Times brand would come to include cannabis products themselves, which killed any remaining legitimacy of the brand as a taste maker—contracting production and sticking the HIGH TIMES label on what was not even the cultivator’s best product.

Less noticed, but of far greater consumer significance was the content of the magazine’s monthly centerfold in the 1990’s and 2000’s. Originally printed as a tweak at Playboy, the High Times centerfold debuted in the first edition of the magazine and featured the same fetish-objectification of its subjects. Importantly, the quality of the cannabis flower pictured in the magazine noticeably changed. Along with the featured centerfold, High Times shared “Pix of the Crop”: reader-submitted photos of the plants they were growing. Comparing featured plant photos from different eras of the magazine’s run shows the changes in the quality of the cannabis flowers being cultivated by “professional” and “amateur” growers, alike. The quality of the marijuana available to a growing number of consumers was undoubtedly improving, due to a combination of increased prohibition and surveillance as well as a growing social movement against it.

Note the quality of the cannabis flowers featured, just 19 years apart. Size, density, and potency were bred into flowers, helped along by policies that led to both more domestic production and to growers moving indoors.

I used theories of social movement, social class, the nation-state, marijuana, and culture to understand and contextualize the unique and defining qualities of the marijuana policy reform movement’s participants, institutions, and resources. High Times was the most valuable resource for exhibiting what came to constitute the marijuana policy reform movement at the end of the twentieth century. There was nothing that better captured what would come to be termed “the culture,” which was in so many ways the name given to the resistance to prohibition itself.