Ordell Robbie: Goddamn girl, you gettin’ high already? It’s just 2 o’clock!

Melanie: It’s that late?

Ordell Robbie: You know, if you smoke too much of that shit, that shit’s gonna rob you of your ambition.

Melanie: What if your ambition’s to get high and watch TV?

The decriminalization of marijuana in Massachusetts, by MPP-sponsored voter initiative in 2008 changed the complexion of marijuana reform advocacy in the Commonwealth. It also changed the makeup of the Massachusetts Cannabis Reform Coalition (MassCann) over the next few years, and the operation of its signature event, the Boston Freedom Rally.

The Freedom Rally has served multiple purposes over its 35 years. At first it was a means of raising public awareness that there were people who supported marijuana law reform, despite the Reagan/Bush Drug War running full-tilt. The first rally event was held in 1989, at a highway rest stop in North Adams, Mass. Organizers moved to the U.S.S. Constitution in Charlestown Navy Yard (it is on Boston’s Freedom Trail and much better for foot traffic) and thereafter to Boston Common, where the Freedom Rally has been staged every year since 1991.

As the event grew in popularity and notoriety (pot smoking on the Common!), the Freedom Rally grew into MassCann’s largest annual fundraiser event and provided the opportunity to exhibit public sympathy for marijuana reform, despite commercial media relying on a prohibition framing in its coverage. Well, commercial media other than High Times magazine; it became a major sponsor, donating multiple pages of event advertising and editorial follow-up coverage, annually.

Washouts due to Hurricanes Ivan and Ophelia in 2004 and 2006, respectively, put MassCann at risk of dissolution. On August 29, 2007, the MassCann board informally agreed that should the upcoming Rally fail to raise money, it would be the end.

By 2007, MassCann was utilizing social media channels such as MySpace, Facebook, and YouTube, to promote activism and spread information. Taking control of media meant coverage of the Freedom Rally was no longer monopolized by state-licensed broadcast institutions. Within a matter of a few years, the purpose of the Freedom Rally, went from trying to put forth a reform message through an otherwise-unfriendly local broadcast and print media to producing an event worthy of national and international attention.

Marijuana prohibition was formally internationalized through the United Nations’ Single Convention Treaty on Narcotics, which essentially made those drugs the United States found problematic, the world’s problem, too. By 2008, while there were a handful of states whose reforms brought forth serious discussion of medicinal marijuana laws, Massachusetts was still without decriminalization. From this state of total prohibition the audacious, public violation of marijuana law gained a political cache.

Police arrested scores of attendees for possession every year. This was another purpose served by the Freedom Rally: To demonstrate the futility of attempting to arrest our way to abstinence. It was a largely symbolic exchange, aside from the material repercussions of a criminal arrest and potential conviction for smoking a joint.

In 2008, marijuana was completely illegal, and over 10% of Massachusetts residents (c. 500,000) consumed it monthly or more often. There were about 12 arrests a day in the Commonwealth; with a noticeable bump on the third Saturday in September. Perhaps one in a thousand Rally attendees would be arrested in a given year. The police lacked the ability (and eventually the desire, it seemed) to enforce the law in the face of mass civil disobedience. They were symbolic arrests, sacrificing good people for the sake of propping up a racist policy whose days were numbered once white, middle class young adults incorporated pot smoking into their everyday practices.

More than any other person, Bill Downing made the Boston Freedom Rally happen for the better part of three decades. Bill was an entrepreneur who loved weed, and he gladly and tirelessly applied his talents to marijuana law reforms. He was also a small-crop cultivator and supplier. When I needed to illustrate how the marijuana wholesale-retail economy was quite different under prohibition than otherwise, I went to my notes on the many interactions we had during my data collection on marijuana culture. Done properly, Bill advised me, one could build credit with a “wholesaler” such that one never had to exchange money for marijuana.

He also picked me, a relative newcomer to MassCann, as his successor to the presidency of the coalition. He explained to me that had been president for fifteen years, he wanted to pursue new business interests, and still have time for his kids. When he asked me if I wanted the job, I said I was not sure. “Perfect! I am glad to hear that,” he replied, explaining that it was a thankless job and anyone who really wanted it would soon find they did not. Indeed. I came to understand that anyone who eagerly wanted the job, by virtue of that fact, would be unqualified for it.

Holding together a coalition of cannabis reform activists under criminal prohibition is a task. In part because of the diversity of the participants. While all of them subscribed to the belief that marijuana should be legal, the greater rubric under which that would take place ranged from Survivalist Libertarian to Socialist. Atheists broke bread with those whose activism grew from devout Christianity and Genesis 1:29 And God said, “Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is on the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit. You shall have them for food.

The common thread was opposition to criminal prohibition; criminal defense attorneys were naturally attracted to the movement, for ideological as well as business purposes. Effective cat herding pounded the fight against prohibition—the specifics of what would come next were not part of the discussion—the motivation was to fight against injustice. How that injustice was contextualized by the participant could be a distraction. I noted this early in my observations, at the 2001 NORML conference, where two presenters—a Libertarian and a Socialist—had a disagreement over WTO protests. A quick reminder they shared a common enemy was enough to move off the topic.

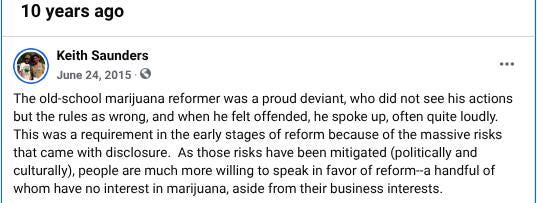

Prior to decriminalization, marijuana reformers were principled actors—even the weed dealers among them sought relief as much for destigmatization as imagined market growth. With the decriminalization vote in 2008, MassCann saw a rise in membership. Removing criminality gave people courage to step out of the closet and speak up. The cultural momentum was shifting in favor of the reforms that would wash over the nation in the coming 15 years. With it came a new quality of reform activist: The classical entrepreneur—one who has no particular care for the commodities they sell (they are in the business of getting rid of them, after all)—began to appear. Unlike the prohibition-era weed dealer or auxiliary industry (glass/paraphernalia) entrepreneur, these folks were looking to get an edge on a soon-to-be legal market.

Bill Downing loved weed more than he loved money, and that’s why those who love the money they have been able to make without risking arrest while selling weed owe him gratitude money cannot buy.